A week-long itinerary across Kyrgyzstan brought us to the shores of two very different lakes. One, the Issyk-Kul, is a gentle and vast sea where families spend their summers and Russian pop music blasts from the cafes on the beach. The other, Song-Kol, perched within a crown of towering mountain peaks, is a shy and grumpy lake where (legend has it) it rains at least once a day.

But most importantly, we decided to get around Kyrgyzstan with no car of our own. This meant we fully relied on however willing Kyrgyz people were to share their country with us.

And they welcomed us with open arms and hearts.

Life on the Issyk-Kul

The plane lands before daybreak, despite the three-hour delay. Europe is thousands of miles away, beyond the steppe, beyond the Urals.

Our hotel is supposed to send a driver to pick us up. The thought stresses me out — is he going to show up? Is it going to be an official taxi? I laugh now as I type out of these concerns. I knew nothing of Kyrgyzstan. Sure, I had looked at its crinkled shape on the map, a small presence squeezed between China and Kazakhstan. But I had no idea what it would mean to be here, breathing this air, a few som in my pockets, and no internet connection on my phone.

It is a perfect summer morning and there is indeed a driver waiting for us outside of the Manas airport. He is a middle-aged man and doesn’t speak a word of English. His ride is a van with right-hand drive and a shattered windshield.

As we head out of Bishkek, we take an eager look out of the window.

The air hitting our sleepy faces carries a very peculiar smell, a smell I would learn to identify as quintessentially Kyrgyz. It is a deep, brown smell of burning and road dust; a dry and earthy odor, much like the smell of a good cigar.

The van speeds east-bound. Our first destination is Kaji-Say, a small settlement on the south shore of Lake Issyk-Kul. We will spend a few days there, enjoying some quiet Riviera life divided between the beach and a few excursions around town.

To our right, barely visible in the haze, are the Terskey Alatau, the Shady Mountains. The few Kyrgyz houses on the side of the road look as if they have been built out of advertising boards (“1 Гб = 1 сом!”, “KYRGYZ COLA”) turned azure by the constant sunlight. Every fifty yards a fruit stand sells piles of watermelons and plastic floaters, even though the Issyk-Kul is still more than two hundred miles away.

We get to the Art Hotel early in the afternoon. It is located in a dusty alleyway off the main road. All around, rugged guesthouses and holiday homes. Everything about the structure is welcoming — the owner Timur with his high cheekbones and bright blue eyes, his wife and son playing in the yard, the coffee they offer us, and our big, clean room.

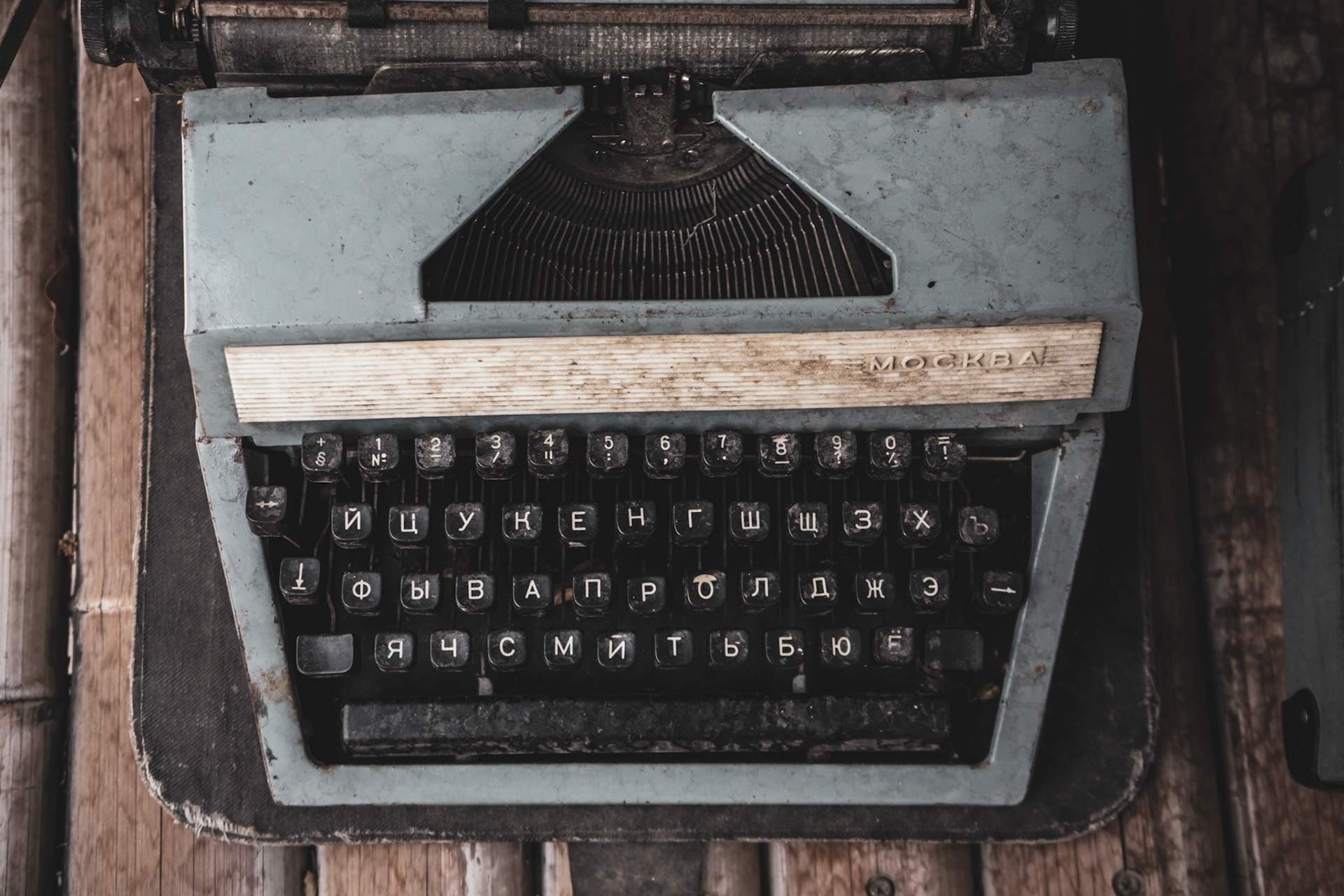

The courtyard is luxurious and it showcases all kinds of memorabilia from Soviet times. As we sit in the shade, we hear the occasional apricot fall with a rustling of leaves and a thud.

“How do we get to Bokonbaev, or to the Shkashka canyon?” we ask Timur.

He shrugs.

“You stop any car that goes in that direction, and hop in.”

“Can’t we rent bicycles?” we ask in return, reluctant to compromise with our very western fear of hitchhiking.

“Have you seen the roads? Just stop a car. It won’t cost you more than one-hundred som.”

He is right. The roads in Kyrgyzstan are damaged, and drivers seem to think that no hole in the asphalt is too big if you drive over it fast enough. In Kaji-Say, most cars seem to come straight from the Seventies; they’re dusty old Ladas with broken seats and washed-out Kyrgyz flags stretched over the windshields. I wonder how those vehicles can still brave the nonexistent streets to this day, but they do, and people just hitchhike everywhere.

Having four wheels to rely upon, no matter how battered, is a source of income here.